Utah

#32 King’s Peak, elevation 13,528 ft.

Reggae, beavers, Land art.

Glamping with my cousin Gary at the “Rise Up!” reggae festival in Heber before we set off for King’s Peak brought me to the conclusion that my fellow Americans, though divided on many fundamental social and politcal issues, are united in one respect, which is that a lot of them really like to get stoned. Not me, but to each his own. So began my last highpointing trip before the onset of the 2020 Covid pandemic and the ensuing years of inactivity that nearly derailed the quest.

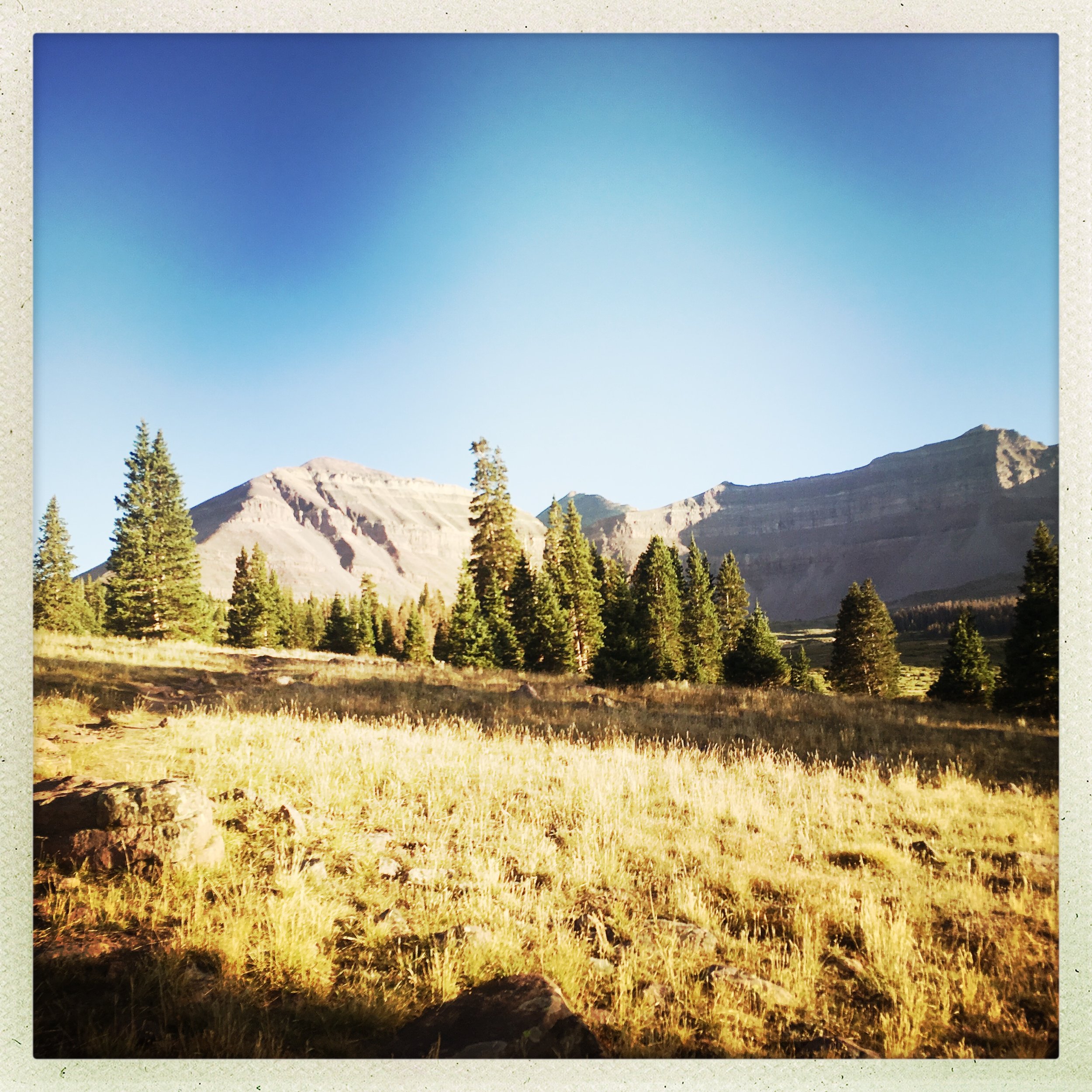

Gary and I drove north and east from his house in Park City to the Henry’s Fork trailhead in the Uintas, the highest mountains in the continental United States that run west to east and the highest without significant modern glaciation. Their name comes from the Ute word for “pine tree” or “pine forest.”

Here is the inimitable John McPhee conversing on the Uintas with Princeton professor Kenneth S. Deffeyes in Basin and Range (1979), the first installment of what would become McPhee’s classic trilogy on North American geology:

He said nothing else for a time, while he tapped at the earth I had uncovered and captured a perfect sample. Then he said, ‘The north side of the Uintas is a spectacular mountain wall. Glorious. You come upon it and suddenly you see structurally the boundary of the range. But you don’t see what put it there. The Uintas are mysterious. They are not a basin-range fault block, yet they have come up nearly vertically, with almost no compression evident. You just stand there and watch them go up into the sky. They don’t fit our idea of plate tectonics. The Rockies in general will be one of the last places in the world to be deciphered in terms of how many hits created them, and just when. And from where.

Up into the sky indeed. That you have entered into bowl, a magnificent natural amphitheater, is readily apparent as you walk south into Henry’s Fork basin. Invariably either blanched or enshadowed in the distance when visible, the isosceles summit of King’s presides over most perspectives along the route. Excited by the precipitous cliffs funneling us south—walking a route I had studied for weeks if not years—I missed the first, most basic and obvious marker of the trail toward Dollar Lake as we entered the clearing: the small footbridge to our left that would lead us over the creek. Instead, we veered right, to the western side of the meadow, which we would later backcross through hip-deep rivulets and slippery tussocks to reach our campsite on the opposite side.

We planned our trek to King’s for midweek in September, after the restart of school, hoping for thinner crowds and better weather. We saw a few people on the trail but none at Dollar Lake, which is otherwise commonly mourned as a victim of extreme overuse: death by picturesque. After setting up camp in a stand of Engelmann spruce, we walked to the lakeshore and watched the silky wake of a beaver pair ripple on the reflections of the cliffs. We stayed until dark to see every glorious shift in color. As we did, back at the campsite an animal, probably a marmot, raided my cousin’s tent and ran off with his satellite phone, which he had intended to use to keep in touch with company headquarters. Nature abhors the chronically online.

From Dollar Lake we hiked south along the main trail the next morning, which is visible in satellite images. We passed a stripped mammal vertebra in the short grass before reaching the upward ramps.

From Gunsight Pass, at almost 12,000 feet, we intended to find and take the alternate path that traverses the lower reaches of the incline, but either I never found that cutoff or it wasn’t—or didn’t seem to b—that much of a shortcut, as we toiled along in the wilds of Painter’s Basin for a good long while. Once out of the basin the trail up was clear, however, and after a snack below the final pitch, at Anderson Pass, we picked our way along the dirtiest rocks showing footfall and made the summit by midday.

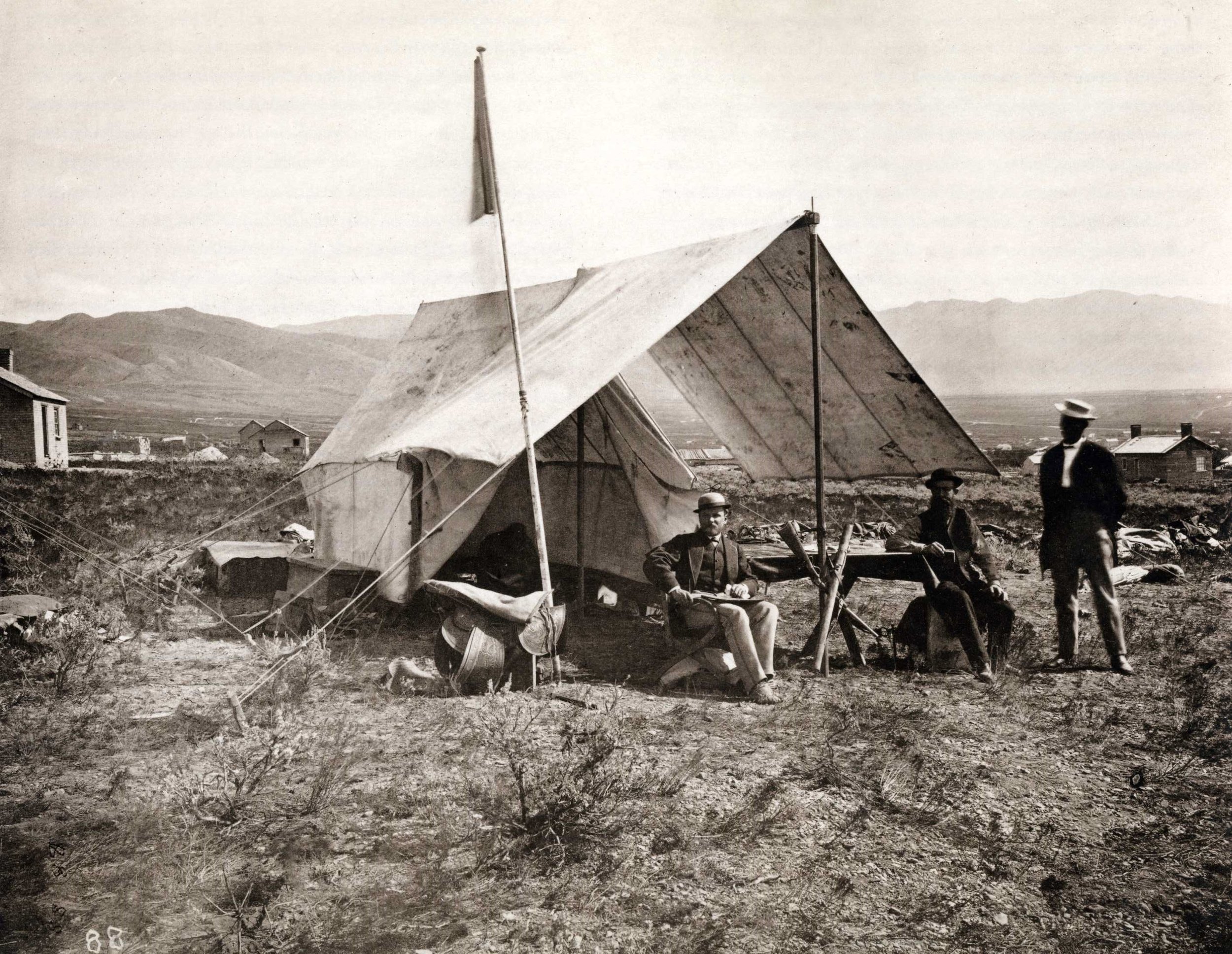

Consider at this point the curious life of Clarence King, the Eastern elite-born first director of the United States Geographic Survey for whom the peak is named. Remembered today for his foundational explorations of the American West, King outran bandits on horseback, hunted buffalo, and mapped the rim of Yosemite Valley, among other feats of adventure. King also fell in love with, and married via common law, a formerly enslaved woman from Georgia named Ada Copeland, “passing” as a light-skinned Pullman porter named James Todd before revealing all to his wife on his death bed. They couple, who lived together happily by all accounts, had five children together at a time when interracial relationships were illegal if not taboo in most parts of the United States.

Clarence King (center) at his camp near Salt Lake City while working on the Fortieth Parallel Survey. Photograph by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, October 1868

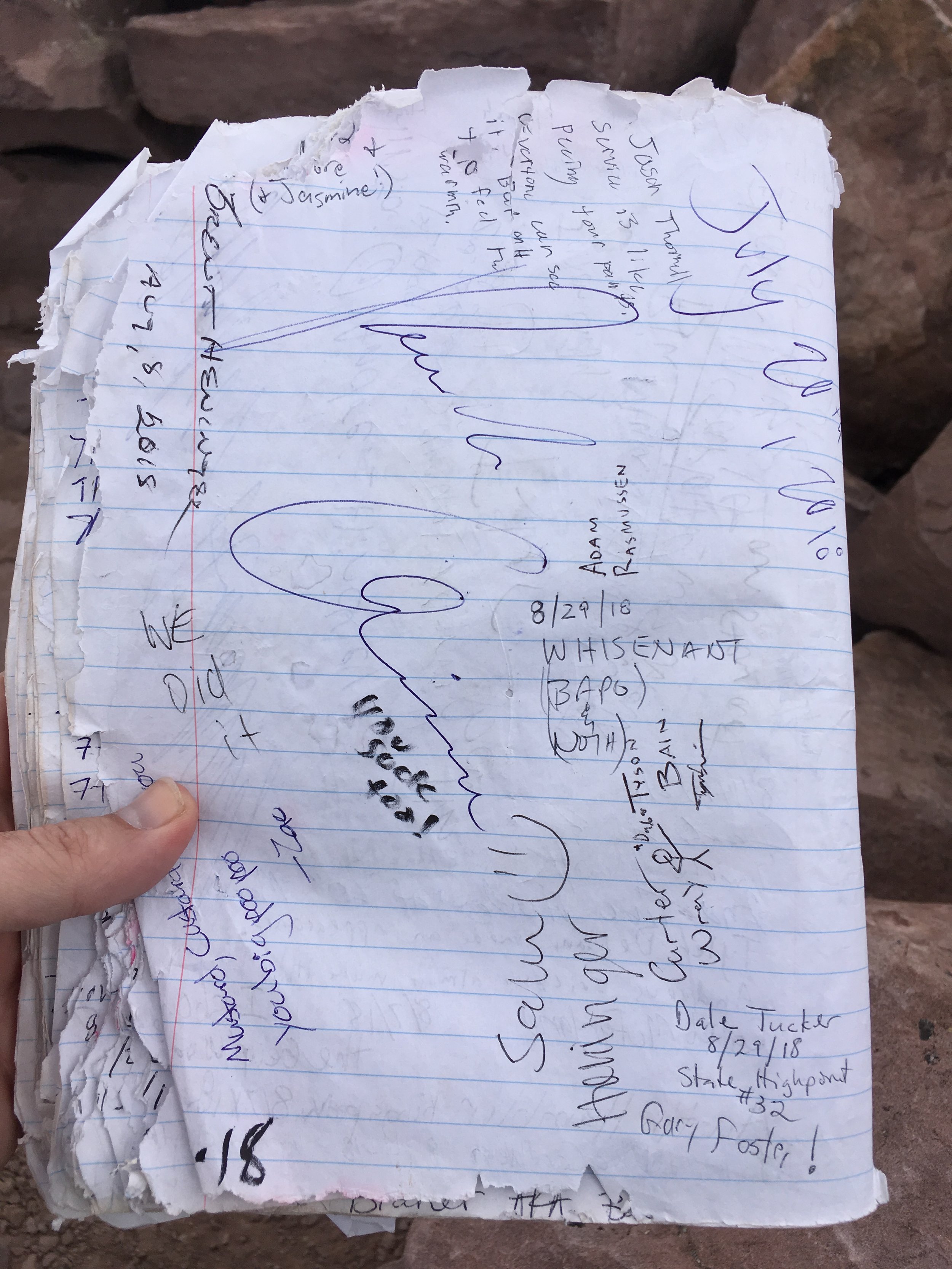

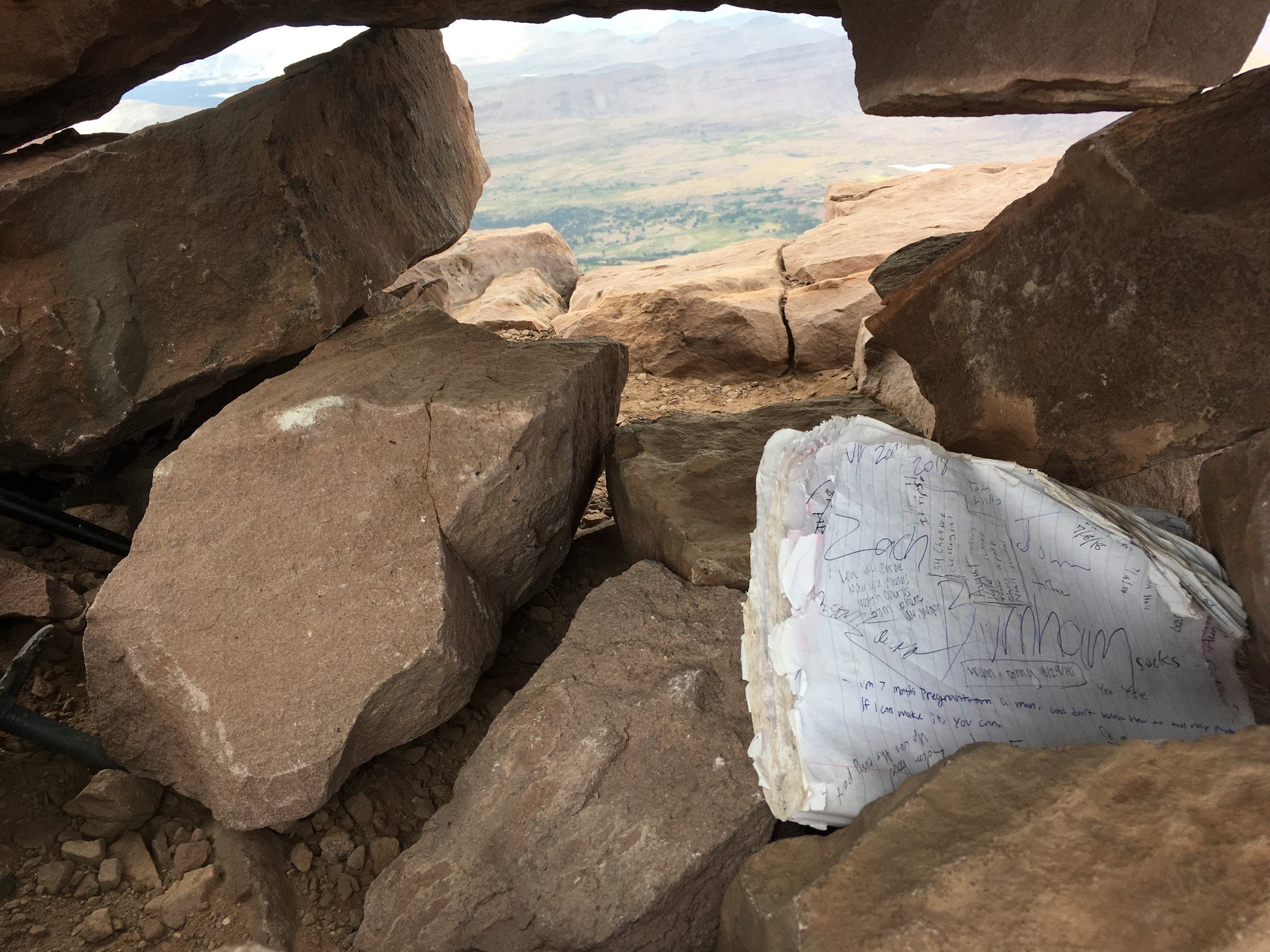

The views from the best-known of King’s several namesake peaks are panoramic and magnificent, but the scattering of lakes below signals the impressive trek back. We signed a frayed logbook stashed under the biggest rockpile, ate, and scrambled down to the main trail on a more direct if boulder-hopping line. The long march home was notable only for the denouement of my ill-considered strategy—designed to save weight on the hike in—of relying on an oversize fanny pack, a mistake that left me limping into our Dollar Lake campsite tired, thirsty, off-balance, and hungry.

Uinta Sheep

Logistically and physically, Kings was the hardest highpoint hike I had done to date. I was fortunate to have my cousin Gary and his wife, Tina, as hosts in Park City. This trip was a second attempt after an earlier one had been canceled because of weather. Gary was my intrepid hiking partner and most excellent trail companion. We don’t have as much footage of the Gunsight Pass portion as I’d like, but we were busy trying to not get lost.